This tutorial will guide you through a moderately complex data cleaning process. Data mining and data analysis are art forms, and a lot of the steps I take are arbitrary, but I will lead you through my reasoning on them. Hopefully from that you will be able see the logic and apply it in your own analyses.

The dataset I will be using for this tutorial is the “Adult” dataset hosted on UCI’s Machine Learning Repository. It contains approximately 32000 observations, with 15 variables. The dependent variable that in all cases we will be trying to predict is whether or not an “individual” has an income greater than $50,000 a year.

data = read.table("http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/machine-learning-databases/adult/adult.data",

sep=",",header=F,col.names=c("age", "type_employer", "fnlwgt", "education",

"education_num","marital", "occupation", "relationship", "race","sex",

"capital_gain", "capital_loss", "hr_per_week","country", "income"),

fill=FALSE,strip.white=T)

Here is the set of variables contained in the data.

- age – The age of the individual

- type_employer – The type of employer the individual has. Whether they are government, military, private, an d so on.

- fnlwgt – The \# of people the census takers believe that observation represents. We will be ignoring this variable

- education – The highest level of education achieved for that individual

- education_num – Highest level of education in numerical form

- marital – Marital status of the individual

- occupation – The occupation of the individual

- relationship – A bit more difficult to explain. Contains family relationship values like husband, father, and so on, but only contains one per observation. I’m not sure what this is supposed to represent

- race – descriptions of the individuals race. Black, White, Eskimo, and so on

- sex – Biological Sex

- capital_gain – Capital gains recorded

- capital_loss – Capital Losses recorded

- hr_per_week – Hours worked per week

- country – Country of origin for person

- income – Boolean Variable. Whether or not the person makes more than \$50,000 per annum income.

The first step I will take is deleting two variables: fnlwgt, and education_num. The reason for this is they clutter the analysis. education_num is simply a copy of the data in education, and though if we were running more advanced analysis we could weight the observations by fnlwgt, we won’t be doing that right now. So we will simply delete them from the data frame. The following code is for deleting a list element (hence the double brackets), and is the most appropriate for completely excising a variable from a data frame.

data[["education_num"]]=NULL

data[["fnlwgt"]]=NULL

Now to begin the data preparation. All the variables that were stored as text, and some that were stored as integers, will have been converted to factors during the data import. Because we’re going to be modifying the text directly, we need to convert them to character strings. We do this for all the text variables we intend to work with.

data$type_employer = as.character(data$type_employer)

data$occupation = as.character(data$occupation)

data$country = as.character(data$country)

data$education = as.character(data$education)

data$race = as.character(data$race)

data$marital = as.character(data$marital)

We should look at the relative frequency of some groups within the variables to see if we should block them.

> table(data$type_employer)

? Federal-gov Local-gov Never-worked Private Self-emp-inc

1836 960 2093 7 22696 1116

Self-emp-not-inc State-gov Without-pay

2541 1298 14

Given “Never worked” and “Without-Pay” are both very small groups, and they are likely very similar, we can combine them to form a “Not Working” Category. In a similar vein, we can combine government employee categories, and self-employed categories. This allows us to reduce the number of categories significantly.

data$type_employer = gsub("^Federal-gov","Federal-Govt",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Local-gov","Other-Govt",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^State-gov","Other-Govt",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Private","Private",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Self-emp-inc","Self-Employed",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Self-emp-not-inc","Self-Employed",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Without-pay","Not-Working",data$type_employer)

data$type_employer = gsub("^Never-worked","Not-Working",data$type_employer)

> table(data$occupation)

? Adm-clerical Armed-Forces Craft-repair Exec-managerial Farming-fishing

1843 3770 9 4099 4066 994

Handlers-cleaners Machine-op-inspct Other-service Priv-house-serv Prof-specialty Protective-serv

1370 2002 3295 149 4140 649

Sales Tech-support Transport-moving

3650 928 1597

On occupation, a simple way to block the categories would include blue collar versus white collar. I separate out service industry, and other occupations that I didn’t see fitting well with the other groups into their own group. It’s unfortunate that Armed Forces won’t fit well with any of the other groups. In order to get it properly represented, we can try up-sampling it when we train the model.

data$occupation = gsub("^Adm-clerical","Admin",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Armed-Forces","Military",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Craft-repair","Blue-Collar",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Exec-managerial","White-Collar",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Farming-fishing","Blue-Collar",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Handlers-cleaners","Blue-Collar",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Machine-op-inspct","Blue-Collar",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Other-service","Service",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Priv-house-serv","Service",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Prof-specialty","Professional",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Protective-serv","Other-Occupations",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Sales","Sales",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Tech-support","Other-Occupations",data$occupation)

data$occupation = gsub("^Transport-moving","Blue-Collar",data$occupation)

> table(data$country)

? Cambodia Canada China

583 19 121 75

Columbia Cuba Dominican-Republic Ecuador

59 95 70 28

El-Salvador England France Germany

106 90 29 137

Greece Guatemala Haiti Holand-Netherlands

29 64 44 1

Honduras Hong Hungary India

13 20 13 100

Iran Ireland Italy Jamaica

43 24 73 81

Japan Laos Mexico Nicaragua

62 18 643 34

Outlying-US(Guam-USVI-etc) Peru Philippines Poland

14 31 198 60

Portugal Puerto-Rico Scotland South

37 114 12 80

Taiwan Thailand Trinadad&Tobago United-States

51 18 19 29170

Vietnam Yugoslavia

67 16

The variable country presents a small problem. Obviously the United States represents the vast majority of observations, but some of the groups have such small numbers that their contributions might not be significant. A way around this would be to block the countries.

data$country[data$country=="Cambodia"] = "SE-Asia"

data$country[data$country=="Canada"] = "British-Commonwealth"

data$country[data$country=="China"] = "China"

data$country[data$country=="Columbia"] = "South-America"

data$country[data$country=="Cuba"] = "Other"

data$country[data$country=="Dominican-Republic"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Ecuador"] = "South-America"

data$country[data$country=="El-Salvador"] = "South-America"

data$country[data$country=="England"] = "British-Commonwealth"

data$country[data$country=="France"] = "Euro_1"

data$country[data$country=="Germany"] = "Euro_1"

data$country[data$country=="Greece"] = "Euro_2"

data$country[data$country=="Guatemala"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Haiti"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Holand-Netherlands"] = "Euro_1"

data$country[data$country=="Honduras"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Hong"] = "China"

data$country[data$country=="Hungary"] = "Euro_2"

data$country[data$country=="India"] = "British-Commonwealth"

data$country[data$country=="Iran"] = "Other"

data$country[data$country=="Ireland"] = "British-Commonwealth"

data$country[data$country=="Italy"] = "Euro_1"

data$country[data$country=="Jamaica"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Japan"] = "Other"

data$country[data$country=="Laos"] = "SE-Asia"

data$country[data$country=="Mexico"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Nicaragua"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Outlying-US(Guam-USVI-etc)"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Peru"] = "South-America"

data$country[data$country=="Philippines"] = "SE-Asia"

data$country[data$country=="Poland"] = "Euro_2"

data$country[data$country=="Portugal"] = "Euro_2"

data$country[data$country=="Puerto-Rico"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="Scotland"] = "British-Commonwealth"

data$country[data$country=="South"] = "Euro_2"

data$country[data$country=="Taiwan"] = "China"

data$country[data$country=="Thailand"] = "SE-Asia"

data$country[data$country=="Trinadad&Tobago"] = "Latin-America"

data$country[data$country=="United-States"] = "United-States"

data$country[data$country=="Vietnam"] = "SE-Asia"

data$country[data$country=="Yugoslavia"] = "Euro_2"

I tried to use a combination of geographical location, political organization, and economic zones. Euro_1 is countries within the Eurozone that I considered more affluent, and therefore people from there are probably going to be more affluent. Euro_2 includes countries within the Eurozone that I considered less affluent. These included countries that are financially troubled like Spain and Portugal, but also the Slavic countries and those formerly influenced by the USSR like Poland. Formerly British holdings that are still closely economically aligned with Britain are included under the British-Commonwealth.

We should block the education variable as well. Ultimately the goal is to shave down the number of categories in the categorical variables. For some methods this vastly simplifies the calculations, as well as to make the output more readable. I choose to block all the dropouts together. I block high school graduates and those that attended some college without receiving a degree as another group. Those college graduates who receive an associates are blocked together regardless of type of associates. Those who graduated college with a Bachelors, and those who went on to graduate school without receiving a degree are blocked as another group. Most everything thereafter is separated into its own group.

data$education = gsub("^10th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^11th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^12th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^1st-4th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^5th-6th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^7th-8th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^9th","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Assoc-acdm","Associates",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Assoc-voc","Associates",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Bachelors","Bachelors",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Doctorate","Doctorate",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^HS-Grad","HS-Graduate",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Masters","Masters",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Preschool","Dropout",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Prof-school","Prof-School",data$education)

data$education = gsub("^Some-college","HS-Graduate",data$education)

data$marital[data$marital=="Never-married"] = "Never-Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Married-AF-spouse"] = "Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Married-civ-spouse"] = "Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Married-spouse-absent"] = "Not-Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Separated"] = "Not-Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Divorced"] = "Not-Married"

data$marital[data$marital=="Widowed"] = "Widowed"

data$race[data$race=="White"] = "White"

data$race[data$race=="Black"] = "Black"

data$race[data$race=="Amer-Indian-Eskimo"] = "Amer-Indian"

data$race[data$race=="Asian-Pac-Islander"] = "Asian"

data$race[data$race=="Other"] = "Other"

Some changes I make were simply to make the variable names more readable or easier to type. I chose to block “spouse absent”, “separated”, and “divorced” as “not married” after some initial data mining suggested they were similar in respect to income.

data[["capital_gain"]] <- ordered(cut(data$capital_gain,c(-Inf, 0,

median(data[["capital_gain"]][data[["capital_gain"]] >0]),

Inf)),labels = c("None", "Low", "High"))

data[["capital_loss"]] <- ordered(cut(data$capital_loss,c(-Inf, 0,

median(data[["capital_loss"]][data[["capital_loss"]] >0]),

Inf)), labels = c("None", "Low", "High"))

Here I block capital gains and losses, rather than do a transformation. Both variables are heavily skewed to the point that I think a numerical transformation would not have been appropriate. So I choose to block them into “None”, “Low”, and “High”. For both variables, none means they don’t play the market. Low means they have some investments. High means they have significant investments. Both gains and losses are positively associated with higher income, because if you have money in the market, odds are you have money to begin with.

It is worth noting that by doing all this blocking, we are potentially losing some information that may be relevant. In some cases this was confounding information. In others, we simply don’t have enough data within a group to make a determination about that group. So we block them with similar groups. In all cases, blocking drastically simplifies the models we use. For categorical variables, on mathematically based methods, the actual calculation sees a dummy variable for each level within a categorical variable. So for example if you have 2 categorical variables, with five and three categories respectively, the calculation will see 8 variables added to the equation. For something like this dataset where the bulk of the variables are categorical, and each of them has several levels, it’s easy to see how the number of variables in the model equation will rise. Blocking reduces this problem.

is.na(data) = data=='?'

is.na(data) = data==' ?'

data = na.omit(data)

Here I’m omitting observations or which we don’t have data in some of the variables. This is a judgement call on my part, but we only lose a couple thousand observations when we have a pool of more than thirty thousand. Some of the methods I will be using can deal with missing data, but some can not. So it’s a good idea at this point to remove observations with missing data so as to not bias any comparisons we make between the methods.

data$marital = factor(data$marital)

data$education = factor(data$education)

data$country = factor(data$country)

data$type_employer = factor(data$type_employer)

data$occupation = factor(data$occupation)

data$race = factor(data$race)

data$sex = factor(data$sex)

data$relationship = factor(data$relationship)

data$income = as.factor(ifelse(data$income==data$income[1],0,1))

At this point, I’m done modifying the categorical variables, so I’m converting them back to factors. The values for income were stored as “>50k” and “<50k". I wanted to convert them to 0's and 1's, but because of the inequality sign in the value, I could not use conditional statements. I therefore checked what the value for income in the first observation was. It happened to be "<50k". So the ifelse statement makes all cells that are equal to the value in the first cell 0, and all other cells 1. Then I convert it to a factor.

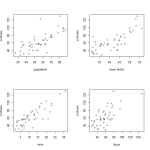

data$age = scale(data$age)

data$hr_per_week = scale(data$hr_per_week)

For the two remaining variables in the dataset, I choose to scale them. This applies a normal transformation. Each value minus its mean over the sample standard deviation. Of course, each sample will have a different mean and standard deviation, so if we wanted to apply any trained model to new data, we would have to make note of what this particular sample’s mean and standard deviation are so as to apply the same transformation. It’s worth noting that neural networks require numerical input variables to be scaled.

sample = rbinom(dim(data)[1],1,.3)

trainset = data[sample==0,]

valset = data[sample==1,]

When comparing classifiers, it’s important to have a constant sample left out that the classifier is not trained on, to see how well the trained classifier will generalize to new data. Here, I am randomly sampling approximately thirty percent of the data into a validation set that I will then use to check the accuracy of my model.

Typically for a paper I will wrap all this preparatory code into a function called dataprep(). I have provided the complete function here for your use. You can invoke it with the following code.

source("https://scg.sdsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/dataprep.r")

The training dataset will be contained in data$train, the validation dataset will be in data$val.

Again, some of the steps I take here are completely arbitrary. I believe there’s sufficient justification for the steps I take in blocking categories here, but I must caution you that overblocking can compromise the data as you may end up removing actual signal, or valid information, within the data.

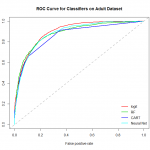

Performance of Classifiers on Dataset

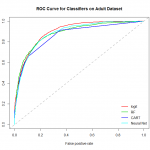

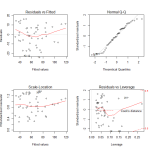

I have prepared some code to demonstrate the relative performance of the classifiers named on this particular dataset, with these particular cleaning steps used. All classifiers used the same data source, the same cleaning steps. For logistic regression, we omitted the “relationship” variable during the diagnostics and model validation phase. Otherwise, the conditions were made as similar as possible. As we can see, on this dataset Random Forest has a slight early advantage, though probably not significant. Once the false positive rate gets above around .2, Logistic Regression takes over as the dominant model.

As we can see, on this dataset Random Forest has a slight early advantage, though probably not significant. Once the false positive rate gets above around .2, Logistic Regression takes over as the dominant model.

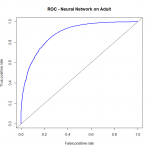

There are of course more things we can do. In much the same way bagging (by way of Random Forest) helped the CART tree, we can do the same with any other classifier. I was intentionally vague with describing the underlying classifier used in bagging, because in truth we can use any classifier with it. For instance, we can significantly improve the results of the Neural Network by bagging.